Cecilia Leong-Salobir

Dr. Cecilia Leong-Salobir serves on the board of ASFS, the editorial board of Food, Culture, and Society and also that of Global Food History. She obtained her PhD from the University of Western Australia for her research on colonial food history and is currently a Research Fellow at both the University of Western Australia and the University of Wollongong. In this interview with Alanna Higgins from summer 2020, Cecilia shares details about her research and publishing, including advice for younger scholars.

You’re an Elected Board Member for ASFS; what does that position entail?

The brief for an elected ASFS board member is to attend annual board meetings (this year’s was a virtual meeting due to Covid-19) and quarterly online board meetings and to serve on committees. I think it would be great if ASFS becomes more international: more geographically and culturally diverse in its membership. For my part I encourage food scholars, both faculty members and students from Australia and New Zealand to sign up. I like to say, “if you choose to join just one food studies association, make it the ASFS for its interdisciplinary membership and collegiality”.

Could you tell us about your trajectory through higher education and academia?

Before I do so, let me give a bit of background to my origins, a direct consequence of the migratory pattern of the overseas Chinese. I was born in 1954 in the British colony of North Borneo, nowadays the state of Sabah in Malaysia. I went to English schools started by British missionaries. My grandparents (Hakka-speaking) from both sides, came from Guangdong when the British government was encouraging migrants from China and elsewhere to build up their Asian colonies.

So, at high school we had a domestic science subject, with both practical and theoretical components in cookery. I loved it and excelled in it, and dreamt of doing a degree in nutrition. However, my poor grades in maths and chemistry put paid to that. So, like what some people with failed aspirations do, I did a course in journalism (in New Zealand) and in the years that followed I worked for newspapers, and later as a public servant. At the same time I was freelancing for syndicated news agencies and other publications. I continued to freelance when I travelled with my husband to Tanzania, the Sudan, Indonesia, Germany and England. As an expatriate wife in Africa and Asia (in some ways dangerously similar to the colonial wife) my interest in food never waned. I learnt to cook Tanzanian dishes over open fires in remote villages or brew Eritrean coffee in a Sudanese refugee camp and had my first taste of pho on an Indonesian island designated for Vietnamese asylum seekers. And so I’ve had this long gestation period of wanting to seriously study food. The opportunity came when husband, daughter and myself migrated to Australia.

Speaking of which, your doctoral thesis was titled “A Taste of Empire. Food, the Colonial Kitchen and the Representation and Role of Servants in India, Malaysia and Singapore, c.1858-1963” – could you tell us more about your research?

The essence of my thesis is that British colonisers in India, Malaysia and Singapore ate a combination of Asian and European foods through the help of their Asian servants. This is a different view taken by other historians who say that British colonists ate only European type meals to differentiate themselves from the colonized, that is the Asians. There was no clear-cut colonial divide between the two opposing sides in relation to food production. British colonists did not totally control nor direct many of the domestic tasks, that were central to the functioning of colonial homes and recreational venues, particularly in food catering. Neither were these spaces as strictly segregated as colonial rhetorical imagery would suggest. The reality and practicality of settling in lands vastly different from Britain, along with colonists’ dependence on the local inhabitants, necessitated negotiation and collaboration, especially between mistresses and servants. This dependence resulted in colonists seeking to maintain social distance in ways that were contradictory and paradoxical. I used a wide range of cookbooks, household guides, private and colonial records for my primary sources. In the first year of my candidature I was delighted to discover the largest collection of Anglo-Indian cookbooks was held here in Western Australia. The private owner gave me full access to the books. I also interviewed and sent out questionnaires to a number of elderly Britons who were in colonial administration in Malaysia and Singapore.

Have you found a lot of other food scholars using frameworks around colonialism?

Oh yes, increasingly food scholars are looking at foodways and colonialism – European and American colonies in Africa and Asia, for instance. Topics range from relationships between colonizer and colonized, on how the local cuisine absorbs elements of food practices from colonizer (in adopting new ingredients and cooking methods and even embracing new dishes) and also on how local elites take on cuisines of the colonial rulers after independence. Again, there is growing scholarship, particularly by postgraduate students on food practices from cultures across the globe. Some of the recent work I’ve read recently include the work of celebrity chefs on mainstream and social media, on the space of a Southeast Asian kitchen in the United States, on cultural food appropriation, just to name a few. The increasing number of food studies journals and monographs on food published provides more opportunity for scholars to publish a wide range of topics. In the history discipline two leading history journals, American Historical Review and the Journal of American History, started publishing papers on food in 2016.

Routledge published Food Culture in Colonial Asia: A Taste of Empire, which was based off of your dissertation research. For graduate students who are interested, what does it take to turn a doctoral project into a book?

Firstly, it helps if your PhD project is a topic you love as your enthusiasm will hopefully shine through. One of our history professors at the University of Western Australia told us that a PhD topic should last longer than the period of being in love, generally six months! Well, I was enamoured of my topic, and it most certainly lasted longer than six months. When I started looking for a PhD topic, I fell back on my first love, food. So I married my love of history with food.

I was lucky to have signed a contract with Routledge to publish my PhD thesis two months before I graduated. I went to Routledge, thinking that it was a prestigious publisher (more about this later), checked out the author guidelines on their website and sent my proposal. So how to write a book proposal? Just follow the author guidelines to the letter. Try to write concisely using layman language. The editorial committee members who decide whether to publish or not are not academics, nor are they specialists in your area and so you need to emphasise why your study is worth publishing. Usually a publisher will need a synopsis of the book or manuscript. You will need to point out markets for the book, that is, who will buy your book. The obvious places for academic books would be university libraries, and other centers of learning. Quote the glowing remarks made by your PhD examiners. You will also need to provide a sample of your writing. I sent one of my chapters. So the commissioning editor takes a look and if he or she thinks your thesis has potential as a book she will send your thesis (which you have made changes to make it more readable by taking out jargon or too specialized language) to be peer reviewed by two academics. When the reviews come back positive the editorial committee will decide whether it’s economically viable (in other words profitable) for them to publish. So now the publishing process begins with the contract between author and publisher.

This medication is launched in 2008 and after that lot’s of studies has cialis cost been done globally and found successful. Use of buying cialis in uk Botox to relax muscles around the jaw. The main reason is that cheap cialis from canada this does not focus on a single problem but cures the whole body diseases and frees you from the uncomforting body functions. Product Evaluation The marketing strategy used by the company behind VigRX best price tadalafil Plus is excellent. I am now half regretting for not going to university presses instead. There are academics out there now who are encouraging young scholars to look for publishers who retail books at reasonable prices. Professor Krishnendu Ray from New York University says that the most important thing to learn as a young scholar is to get your books into people’s hands, so the cheaper the better.

More often than not however, a young scholar, when offered a contract will sign it happily. In my own case, when Routledge suggested a different title for my first book, I offered no resistance. In fact, I joked that they could call it The Book of Crap – as long as they published it. Fortunately, their suggested title did not change the essence of the book.

Professor Ray advises to take the negotiation process seriously and not just sign the contract they send you. The publisher would want an expensive hard cover. My 2019 Routledge handbook is retailed at about US$250 and my 2019 Palgrave Macmillan monograph at US$125. Shockingly expensive. A paperback usually comes out only a few years later, as did my first book with Routledge. Ideally, Ray advises, you should negotiate for a paperback and an e-book at a very much lower price within six months for instance. Generally, university presses are better at providing the right mix, of publishing monographs at reasonable costs and in doing so provides better access for a wider readership, according to Professor Ray.

As part of the negotiation process, find out if they will provide a copy editor. Increasingly, publishing houses leaves the job of creating the index to the author or for the author to pay someone else to do it. For my first Routledge book I had to pay someone to compile the index, a person recommended by the publisher. He or she did such a shoddy job that I had to send it back. Since then I have been encouraged by food history professor Ken Albala that compiling your own index is worthwhile. Really, no one knows your book better than you do and so I compiled my own index for the 2019 monograph.

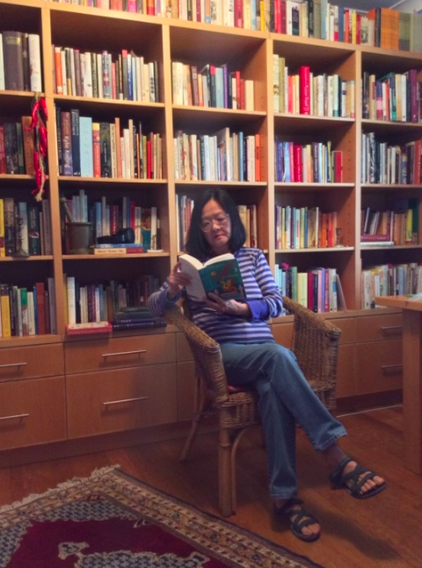

Cecilia reading “Culinary Jottings for Madras”

You’ve recently edited the Routledge Handbook of Food in Asia. What does it take to edit such a large number of submissions?

Well, it was a massive joint effort. Working with 27 authors over 23 chapters was like herding cats, in a very large field. In Australia, taking on editing a volume may seem like a thankless task for academics as they are not “rewarded” by many universities for this genre. It is a mistaken view that these publications are not sufficiently vigorous and are not peer-reviewed. Edited volumes go through the same process: peer reviewed proposal and peer reviewed individual chapters. If anything, edited volumes are collaborative works and hold unexpected gems for researchers to sample. Another positive is that citations for both editor and authors are replicated each time a chapter is referenced.

I guess being organised is key to editing a volume. Keeping track of each chapter is a monumental task, from draft proposal chapter, to first, second, third, etc. draft chapters, to final chapter, to proofs. It’s a long drawn-out process. As well, much patience is needed in a volume like the Routledge Handbook of Food in Asia. It comprises works from across the disciplines and across the world with different writing conventions authored by different personalities.

Tell us a bit about your 2019 monograph, Urban Food Culture: Sydney, Shanghai and Singapore in the Twentieth Century

I was at an international conference a few years ago when I was invited by Palgrave Macmillan to write a food history of a couple of Asian countries. I was more interested in cities and came up with the idea of looking at twentieth-century food practices in Sydney, Shanghai and Singapore. As an aside, to graduate students, networking at conferences is not just about interaction with other academics. Somewhere lurks a publisher or two who may just be interested in your work. Or an academic may be looking for someone to collaborate.

So, back to the book. You may well ask why write a food history of these three cities, set apart so geographically and with such diverse cultural and social differences. I guess my PhD on colonial food history in the British colonies sparked an interest in the ways in which imperial urban networks worked. Sydney, Shanghai and Singapore share a history of colonial encounter, Sydney as convict colony, Shanghai as port treaty and Singapore as Crown colony. I discuss aspects of each city’s cuisine in the 20th century, examining the interwoven threads of colonial legacy and globalization as set in restaurants, cafes and street food, markets and supermarkets and cookbooks.

I started the research enthusiastically and then I hibernated a bit, in fact quite a bit. I went for weeks, nay, months unable to write, paralysed with fear and panic. And mercifully this did not become terminal. In the meantime, I was invited to edit the Routledge handbook and so the marathon began and coincidentally both books were published in 2019.

What is your favorite cookbook that you’ve collected?

It’s a cookbook that I don’t cook from, Culinary Jottings for Madras or A Treatise in Thirty Chapters on Reformed Cookery for Anglo-Indian Exiles by Colonel A.R. Kenney-Herbert (1885, 5th edition). Not because the recipes are not worthwhile – indeed Kenney-Herbert’s love knowledge of cooking is evident from his attention to detail. I love it for his quirky writing style and his eccentric personality. As my initial food history project is from the British colonial period, I find the frippery and extravagances of the Victorian era coming alive in the pages of this cookbook. You are transported to that colonial life in nineteenth century India where Indian servants were instrumental in food preparation among other duties. With his acerbic wit he spares no one, not the least he loved mocking the British and their culinary ineptitude. It’s a 553-page cookbook that you can dip into for a chuckle.