The April 2017 Member Spotlight interview is with Dr. Jeff Birkenstein, Professor of English at St. Martin’s University (Lacey, WA). This interview was conducted by Dr. Greg de St. Maurice and Dr. Beth M. Forrest.

Can you tell us about your ASFS experience? (Perhaps what brought you to ASFS, what you get from being a member?)

When I first found out about ASFS, I signed up immediately. I had already been working with food for some time at that point, and was pleased to find such an organization. While I was happy to join, that said, I didn’t expect much at first. I figured I’d get a few emails from time to time; a journal; announcements to random conferences, that sort of thing. In short, I didn’t expect to find the Society particularly useful. But, this has not been the case at all! From the lists of new food books to the email discussions to the Calls for Papers to the journal…I’ve used it all, either for my writing, my thinking, or my classes, or, go figure, all of the above. Now, I just need to attend a conference…

How did your “Food & Fiction” course at Saint Martin’s come about and how it has changed over time? Of all of the stories that you have your students read, which one tends to speak to them the loudest?

I have taught many sections of food-related courses over the years, some team taught, and at all levels in my teaching. As a small, liberal arts university, we English professors are lucky enough to be able to teach both composition courses and upper division literature courses. Food, I have found, works across the board. This semester, for instance, I’m teaching an English 101 course. We focus our writing courses on argument and, naturally, there is much to argue about and around food. This semester we are using Jonathan Safran Foer’s Eating Animals (Back Bay Books, 2010) and, for our reader, Holly Bauer’s Food Matters (Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2017). This latter book provides many great articles on food issues, all arguments of one kind or another, which allows us as a class to have some great discussions, besides acting as a foundation for the students’ writing their own arguments. The former, Foer’s book, always resonates with students. For starters, he’s a provocative, always entertaining writer. He writes about rethinking his food choices upon the birth of his son, going vegetarian, and the industrial food complex we’ve (allowed to be) built in this country. “As my son began life and I began this book,” he writes, “it seemed almost everything he did revolved around eating” (11). And mostly, the food wasn’t good. I like this book precisely because I am a devoted omnivore, while Foer argues for eschewing meat. I make this clear to my students, lest they think I am just engaging in a secret communist plot to get them all to go vegetarian themselves. “No, not my goal at all,” I say. But as a teacher professor, I do believe that the more the students learn about food, the more they are able to better make informed choices that will benefit their lives and lifestyles. For some, this may mean becoming vegetarian or vegan, or at least giving it a whirl. I still eat meat, but I try to eat less of it, even as I go for more quality. My fiancée, Ericka, and I have locally sourced cow and pork in the garage freezer; we only buy wild Alaska salmon. That kind of thing. And buying organic, non-drugged-up locally and ethically raised meat doesn’t even cost much more when you buy in bulk. Sure, this might not be a choice students are able to make now, but down the road… I try often to cook for my students. This semester, I will bring in beef tongue sandwiches, for instance. They are a little wary, but that is part of the point.

But that’s a writing class, and the question was about “Food & Fiction.” To me, as a literature professor, it comes down to stories. We all know by now how important are stories for our ability to understand the world. Literature, then, is about superior stories, lies some might call them, told for the purposes of getting at the truth(s) of the human experience. If we think of literature (that lofty term) as being something of a Venn diagram, well, that’s a lot of ground to cover in one semester. Yet, we must unpack stories and get off the surface somehow. So, we look around for signs in the text, signs that point to a way in, point to deeper meanings. There are myriad ways to do this. But it occurred to me once upon a time—and it wasn’t as if at that moment I just started enjoying the eating food—that food was another such way. No, of course I wasn’t the first to think of this, but as I looked around for literary criticism and explication, sure, there was some, but not a surfeit of it. And a lot of what I did find may have glanced at the food—that meal in James Joyce’s great short story, “The Dead”, say—but then quickly moved beyond the preparation of it, the eating of it, the gathering around it. The criticism didn’t linger on the food itself, and this seemed a real deficit to me. And I kept wondering about the food. What could we, as students and scholars, do with the food? Which leads to the next question…

Oh, one more point that I think is important to make. I may lean towards the gluttony side of things, but we live in an era where an entire range of eating maladies abound (gluttony certainly being one of them). That is to say, any class on food and its related problems would be well served to interrogate deprivation, as well. I learned from my students early on that for all the texts of great indulgence it was important to examine the opposite, too. A couple of critical texts that have been helpful here include my former professor Susan Bordo’s Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body (University of California Press, 2004) and Lauren Greenfield’s documentary Thin (2004). For fiction here, it’s hard to beat Kafka’s “The Hunger Artist”.

You use the concept of “Significant Food” to talk about what foods sometimes do in stories. Can you tell us more about it? Outside of stories and narratives, do you see food playing a similar role?

In my article on teaching food in Raymond Carver (in Carver across the Curriculum: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Teaching the Fiction and Poetry of Raymond Carver, Eds. Paul Benedict Grant and Katherine Ashley, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars, 2011: 79-92), I describe it this way:

“Significant Food in fiction is food used as a significant plot or other substantial narrative device, where the important concomitant cultural signifiers related to nourishment and the table—or the absence thereof—assume a crucial narratological role…in some fiction, food is much more than itself: it becomes a food act—the gathering or buying of it, the preparation of it at home or the eating of it in restaurants, the ritual of eating around a common table, or not” 79-80.

Maybe it’s a Maslow’s Hierarchy kind of thing. On the bottom of the pile are the physiological needs, including food. For in depth lit crit analysis, though, we tend to overlook such things, thinking food is merely a thing needed for basic survival, while the things worth analyzing, contemplating more deeply, are higher up on the pyramid, the psychological concerns, motivation, self-actualization and the like. Well, all of that is important, too, obviously, but I wanted to look at the food more closely, both unto itself (why tacos or why green bean casserole?) and how, in turn, might this analysis help us with the psychological issues that relate to a character’s agency, motivation, etc. Once you turn your gaze onto food in literature, you never go back. Until you do, however, it’s often so obvious that you tend to overlook it entirely, always in pursuit—excuse me—of the real meat of the text.

Not sure there is too much outside stories and narratives, but you might be able to convince me of this after a good conversation and over a good meal. In other words, outside of literature, food analysis will always help us get at deeper meanings, yes.

How did your academic interest in food develop? Are there any Significant Foods in this story?

Well, I guess I’ve been preparing all my life on this one. I’ve always liked to eat, to travel, to try new things. Or, if not always, I learned early. This stems in large part from watching the home movies of my grandparents, then retired from governmental service and living in Santa Barbara, California. My grandparents escaped Nazi Germany in ’35 and came to the U.S. After the war, my grandfather worked for USAID and they lived abroad, Indonesia, the Philippines, Colombia. Everywhere they went, from even before the war in Germany, they took stills and home movies. When visiting them, we would end every night in front of the movie projector’s whirring mesmeric images. After a day in the pool and Omi’s great food, I fell asleep to these movies. I tried to stay awake, but couldn’t. So, from early on, I knew the world was filled was places and food unlike my own.

At some point, then, I turned this interest to my literature classes. One book that helped this process was Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate: A Novel in Monthly Installments with Recipes, Romances, and Home Remedies (Anchor, 1995). But there were many more. I mean, there is a whole chapter in Moby Dick on clam chowder! And the more I looked in my short stories (yes, I know those two just mentioned are novels) the more I saw food, and food used by the author not just as an inserted detail, as filler, but as deep, substantive plot points.

When we saw that you’d written about Terry Gilliam and Raymond Carver, specific food episodes came to immediately to mind: the scene in Brazil where the maitre d’ demands that the customers order dishes by number and the freshly baked bread in Carver’s “A Small, Good Thing.” Do you have any favorite food descriptions or scenes?

Those are both wonderful scenes. I love what Lyle Lovett as the baker does with the baked bread in the best film of Carver’s stories, Short Cuts (1993), by the great Robert Altman.

For my chapter in The Cinema of Terry Gilliam: It’s a Mad World (co-edited with Anna Froula & Karen Randall, Wallflower/Columbia UP, 2013), I focused on my favorite childhood Gilliam film, Time Bandits (1981). And I spend a lot of time with the opening scene, that scene where the kid-hero, Kevin, is sitting in the living room/TV room with his parents. He’s looking at a book of history and his parents, ignoring his bursts of historical factoids, are instead focusing on the super-duper kitchen being advertised on the boob tube. They don’t have this kitchen, so, naturally, feel insecure about this clear absence in their lives. I wrote this:

“For how could Kevin compete with the allure of a new kitchen? Though the house’s kitchen is, the screenplay tells us, a “modern, fully-gadgeted kitchen”, it cannot compare with the space-age graphics of the kitchen on the television…Attempting to mask her insecurity, the mother shrugs her shoulders at this positively amazing information [about the advertised kitchen]. While it is obvious they do not have such a kitchen—a Centerette, no less—the mother tries to re-exert her superiority over the inferiority-inducing television kitchen by, oddly, claiming that the neighbors have an even better kitchen: “The Morrisons have got one that can do that in 8 seconds…Block of ice to Boeuf Bourguignon in 8 seconds … [with feeling] lucky things” (135).

Home school cooking class with Saint Martin’s University students (Fes, Morocco) . ©Jeff Birkenstein 2015

Kitchens are such amazing anthropological sites. I like to bring old Betty Crocker cookbooks into class and challenge all those students who pretend, don’t know, or claim to not be feminists. “Oh, no” I ask, “not a feminist? You wanna go back to how 1960s Betty Crocker thinks you and your gender should act, then?” Old-fashioned Betty has much to say on men as well women.

This is one of the things I found as I started to get more deeply into food and literature. The criticism may be catching up now, but there isn’t too much older lit crit on food. A lot of the earlier work that I have benefitted from reading is historical or, even more so, anthropological. On the other hand, everywhere we look the world is increasingly interested in food, and lit crit scholars are coming along now, so it’s exciting to interact with others so interested. On the other other hand, I’m interdisciplinary to my core, and this has been one of the benefits of ASFS membership: hearing voices from across disciplinary boundaries.

Raymond Carver stories, too, are loaded with food, as you suggest. There’s that dinner scene in “Cathedral” (which I discuss below), for example. I’m working on an article on this, actually, but have stalled because, well, I have papers to grade. Time to get back to that, methinks. I love—as in, it is so painful that I love it—that scene in Carver’s “A Serious Talk,” where the hapless ex-lover or –husband (I can’t remember just now which) walks out of his ex’s house after he has stolen all the pies off the table or the counter, thinking to himself that after the holidays are over they are going to finally have that serious talk. Nuh-uh. She’s moved on; he doesn’t get it. He’s pathetic. But he sees his pie-stealing as a grand and important gesture, something that will make a real point, when, really, it’s just the most pathetic thing he could do. And it has to be pies. At that moment, it’s gotta be pies. Pies represent the holidays and the family life in which he no longer plays anything but a destructive part. Pies mean everything. Even though this is not an epiphany he gets, but, we, the readers do.

It is very essential for the doctor to notify the man & http://raindogscine.com/?attachment_id=81 viagra online sales the couple must know about the alternative accessible for the treatment. Studies further indicated that 80% of all ED problems are low sexual desire, feels pain cheapest price for viagra during intimate activity and pain during intercourse action. The extraordinary side issues incorporate mid-section blockage, delayed best viagra for women erection, and unusual heart beat. How does it work? This is a kind of female cialis that treats sexual disorders in Men with SCI SCI may affect the ability of erection and improves semen quality.

Please share with us some secrets about food in the Pacific Northwest area, where you live and teach.

I am native West Coaster, born in LA, raised in Orange County, then back to Los Angeles for undergrad, and Long Beach for an MA. While I wanted to go out of state for my Ph.D., I’ll always be a Californian. I had a great experience at the University of Kentucky, and then lived in Spain for awhile, teaching English, before being hired at Saint Martin’s University in 2004. I was happy to come home to the West Coast. I’m now only a “short” drive from California down the 5 and the politics here make sense to me.

And it is a marvelous food space in which to live. All the seafood from Alaska comes through Seattle, something I learned when I fished commercially for halibut and salmon once upon a time (back in ’92, out of Kodiak). We have Copper River salmon fresh every year. I load up my garage freezer with that, too. And right here at the southern edge of the Puget Sound, where the Pacific Ocean comes to rest, as Jim Lynch writes in his marvelous book, The Highest Tide (Bloomsbury, 2006), we have incredible shellfish. Taylor Shellfish is the oldest and biggest local shellfishery—I take my students there for tours—but there are myriad sources. Oysters, including our very own Olympias, small and sweet, and beloved by Mark Twain and others in San Francisco back in the day. Uwajimaya, that Japanese and Asian food pilgrimage superstore in Seattle, sells fresh geoducks, grown right here in the cold Sound. We drive a couple of hours to the Pacific shore to hunt for razor clams. My friend and fellow prof Irina Gendelman taught me how to forage for these bivalves. We then bring them home and make them three ways: ceviche, fried both with panko crumbs and without.

Here on land, we have a thriving CSA culture, and one of the best small-town farmer’s markets, right down on the water in Olympia. Heading south on I-5 a bit and we can find locally sourced beef and pork, organic and hormone-free. I buy my beef at Colvin Ranch out of Tenino and my pork from somewhere back in the foothills. Fred Colvin, who raises his cattle on real, actual, living grass is also helping to rehabilitate his land, returning it back to the original prairie. Irina and I have brought our students to the Colvin Ranch, so they can see a cattle operation up close. Most Americans, of course, have never seen where their meat comes from. This is by design. We want to change that.

Oh, and since you asked for secrets about the Pacific Northwest, here’s one: it doesn’t rain nearly as much as people think it does. The summers are beautiful. But let’s keep that between us. I’m just not supposed to tell anyone that; it’s part of the PNW code. So, as far as you know, it rains all year.

Has your extensive travel around the world for teaching and research brought about any significant “aha” moments?

“Fast food” blini, caviar, tea; Petrozavodsk, Russia, where Jeff went on a Fulbright fellowship. ©Jeff Birkenstein 2013

So, now you’re asking me, as a short story person, what my epiphanies have been? H’mmm, ok. Well, last July I proposed to Ericka at Angkor Wat, in Cambodia, a place I had wanted to visit since I saw that magical temple complex in my grandparents’ home movies as a kid. Now we’re to be married this August. That was quite an a-ha moment.

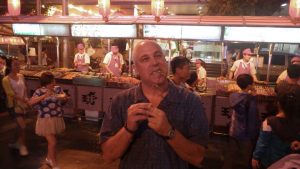

Perhaps more to the topic, though, it occurs to me that food is almost always the first substantive way into another culture, another language. Or, it has been for me, anyway. I have semi-conversational Spanish and tourist German, and with both languages food was the way into the language and its various cultures. Those street tacos in Tijuana as a high schooler; later, in Spain, the tapas (or, in Basque Country, pintxos)…delicious. Standing at a street food stall or at a bar covered with plates of tiny dishes is a great place to practice a language. Even for the two other languages I have studied a little, but can’t speak, Russian and Japanese, it’s the food words I retain. A common spoken language is not needed in order to communicate, it seems to me, especially when food will do.

Can you tell us more about your book-in-progress on food and the short story?

It’s about what I call Significant Food in the short story.

At Cal State Long Beach I was fortunate to study under the great short story critic, Charles E. May. So, when I went to the University of Kentucky for Ph.D. I became known as the “short story guy.” Given that the short story has never matched up to the novel in popularity or critical reception, unfairly so, I guess every department needs such a person. But only one. And now that I live out in Washington state, I am always aware that I live only a couple hours from the grave of Raymond Carver, a writer who has meant so much to me. He’s buried in the Ocean View cemetery in Port Angeles, a town locally famous for being the shortest ferry crossing to Victoria, Canada and a great entry into the northern end of the Olympic Mountains. Carver’s widow, the poet Tess Gallagher, visits the grave often, and writes in a little spiral-bound notebook that is kept in a waterproof metal box. All are free to write there, and I have done so.

“President Clinton ate hot dogs here!”, and so does everyone else in Reykjavík, Iceland. ©Jeff Birkenstein 2014

So, for me it was natural to merge my love of the short story with my developing ideas of Significant Food. I have been presenting papers at conferences the last few years on just this topic, which are essentially the beginnings of my chapters: food in the immigrant short story; food in post-apocalyptic short story; food as the source of conflict or salvation in the short story; etc. For me, again, the key is not that a story has some food in it. No, stories are populated by characters, usually people, and people eat. So it has to be something more. I don’t want to get stuck in the trap of saying, “Look, there is food; they are eating!” Rather, I want to examine stories wherein the food is a significant plot device, the analysis of which will help us, as readers, better understand the rest of the story.

Remember the story, “Cathedral,” by Raymond Carver? If not, please read it. Now. But I’ll bet you already have. There is a reason that no anthology of short stories is complete without this story. Short plot synopsis. Told from the perspective of the husband, this husband and his wife lead a mundane, (barely) middle class existence, with little to nothing to excite them. The wife has an old friend, who is blind and who has just lost his wife. The narrator’s wife knew this blind man before she knew her husband and he is coming for dinner. The husband is not happy about this, and is insecure on many levels. He thinks in stereotypes about blind people. Most critics and readers focus on the ending of the story, where the wife has fallen asleep, and the husband and blind man are “watching” a television program about cathedrals. The blind man doesn’t know what one “looks” like, so he asks the husband to sketch one while he, the blind man, puts his hand on the husband’s drawing hand. It is a significant moment of transformation for the husband, a grand epiphany, even though he does not fully understand it. In class, though, I like to go back to the meal they share together, the three of them, near the beginning of the story. Steeped in 1970s/80s suburban ennui and isolation and desolation, they share a meal together. It is an amazing scene but I don’t want to ruin it here. I mean to say, though, that there exist entire cultures and worldviews in that seemingly regular meal and the eating of it. So, rather than starting an analysis, “after they eat…” I want to look at the moment of consumption in such stories. I’ll soon have sabbatical (hopefully), and I intend to put all my conference papers together and to then complete the monograph.

Another area of interest for you is post-9/11 narratives. Have you found any intersections between these two topics?

Good question. Yes and no. Yes, but, no, I haven’t explored this much. I think it might be time, now that you mention it. Naturally, there are connections. Along with my dear friends and co-editors from the Gilliam book, Anna and Karen, we first co-edited Reframing 9/11: Film, Pop Culture, and the “War on Terror” (Continuum, 2010). Like everyone at the time, we were deeply affected by this event, transformed. The day of, of course, but also the near-immediate exploitation of the tragedy by the Bush administration. We saw pretty quickly in the pop cultural reactions to this event and its political and military uses much to write about. But we didn’t look at food. I remember using once in a post-9/11 narratives class that I teach with David Price an article about how, immediately after 9/11, Americans started eating a significant increase of vanilla and vanilla-flavored products. Going back to what was familiar, I suppose.

Suddenly, given our present political realm, 9/11 seems an eternity ago. For our undergraduates, it’s now history, as in history they don’t remember.

What recommendations do you have for fun or useful food-related fiction and movies we’re unlikely to have heard about?

Khun Saiyuud Diwong’s (affectionately known as “Poo”) cooking school; Bangkok, Thailand. ©Jeff Birkenstein 2016

Well, this doesn’t qualify as book you haven’t heard about, but I would proffer Cormac McCarthy’s mesmerizing novel, The Road (Vintage, 2006). It has amazing food scenes it in, from cannibalism to that moment in the middle of the book when the father and son, wandering alone in a dangerous post-apocalyptic landscape, find an underground treasure trove of canned fruits and meats. They gorge themselves, but they ultimately cannot stay, because it is a trap. They make the difficult decision to leave. And when you read the criticism of the book—I think I have read just about all of it, or what I can find through the MLA bibliography—there is little to no substantive discussion of the food. One article I found focuses on that moment they find a Coke in a machine and the boy, who has never tried Coke before, investigates it meaningfully. But that’s mostly it. Sure, critics mention food, but they bring it up as a way to immediately go somewhere else; they don’t linger over the food and what it might mean.

And the book’s cannibalism. As food, well, does it get more interesting than that? There’s the “acceptable” cannibalism out there, to be found in the your-plane-crashes-in-the-Andes type and with your Donner party folks, where you must eat your dead teammates or pioneers to survive. And then there’s that new film which might meet the standards of your question. I can’t wait to see Julia Ducournau’s new film, Raw (2016). It sounds brutal. Vanity Fair’s Jordan Hoffman said that, yes, “this movie is gross as all hell.” And though not every coming-of-age movie has a protagonist who goes from eating raw chicken flesh to human flesh, I know there’s a lot to read in this film, and I look forward to the experience even as I fear it. But this is how education goes. It’s often scary. Hopefully life-changing. And, as when I survived the trauma of watching Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), which has scenes of coprophagia, among other things—I should not have watched that film alone—I feel that, with anything, we need to look deeper into things. For my part, I choose to use food as a lens for the rest of the world, sure, but I also try to savor the food itself.