What is your favorite memory of ASFS?

I remember vividly my first conference, in Portland, Oregon in 2005. I had recently learned about the ASFS after “discovering” that there was a sociology of food and developing a new course on the topic. (As a graduate student at the University of Washington in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I had no idea that food might be an object of sociological study.) The Portland ASFS conference was an intellectual and culinary delight. I didn’t have a paper to present—I was there to absorb the vibrations of scholars from so many disciplines who shared my newly defined interests. I toured the Willamette Valley wine country, near my alma mater Linfield College. When I attended Linfield in the early 1970s, much of that region was still hazelnut groves and turkey farms, so I was astonished at the growth of this new viticultural industry.

Memorable moments with the ASFS are so many, but most are related to the tours and special events at the conferences. Some favorites: touring farms on an island near Victoria, BC; a laid-back boat trip to Gulf Coast oyster beds while in post-Katrina New Orleans; a stormy trip to Plimouth Colony at the Boston meeting; an Amish dinner at the Penn State meeting; a fabulous tour of interlocking farm, garden, and food provision organizations in Bloomington. No favorite memory—many favorite memories. And so many great people I have met along the way….

Memorable moments with the ASFS are so many, but most are related to the tours and special events at the conferences. Some favorites: touring farms on an island near Victoria, BC; a laid-back boat trip to Gulf Coast oyster beds while in post-Katrina New Orleans; a stormy trip to Plimouth Colony at the Boston meeting; an Amish dinner at the Penn State meeting; a fabulous tour of interlocking farm, garden, and food provision organizations in Bloomington. No favorite memory—many favorite memories. And so many great people I have met along the way….

Your background is sociology—how did you come across food as a research area?

As a sociologist I began my career studying child abuse and its consequences for adult crime. As my career wore on, this area of research became exhausting and unappealing. An after-hours chat around 2002 with a colleague (aided by his discreetly-stashed office bottle of Jack Daniels) meandered around my future: how could I reinvigorate my professional self? Did I have any interests that might inspire a new line of study for me? Well, yeah, food and cooking.

Growing up, I had learned to cook in self-defense, as my mother was a well-intentioned but terrible cook. TV’s “Galloping Gourmet” Graham Kerr was a beacon of cooking inspiration in high school. Over the years I had read cookbooks, created recipes, and watched the new celebrity chefs on TV avidly. My own struggles with weight had sensitized me to our obsession with thinness and body image. So, my friend asked, is there a sociology of food and eating? A quick Google search revealed that, of course, there was and had been for quite some time. Within days I began to develop a new undergraduate seminar on the sociology of food that would allow (and force) me to dive into the field headfirst. For research, I focused initially on obesity and the thin ideal, but I rapidly found myself drawn into broader food-related sociological issues.

We notice that your teaching and research areas include both food/eating and crime/deviance. What are the ways in which these areas overlap?

One of my favorite topics in the sociology of deviance is stigma, as conceptualized by Erving Goffman. His concept has been highly influential in discussions of body image and obesity; people deemed “too fat” experience discrimination in the work place and are subject to daily criticism. Body size is a morally freighted issue, and Goffman discusses the “moral careers” of people deemed deviant by society. Sadly, our society continues to define people by weight and body shape. Fat-shaming is still an “acceptable” form of stigmatization, made even more prevalent by social media. I don’t know how to curtail this trend. Social media enables the trolls, the body shamers.

Do you have any “deviant” food habits—cooking, eating, or otherwise—that you’d like to confess to us?

First, on the serious side: Like so many people, I was raised (implicitly, not explicitly) to see eating as a moral behavior. Overeating, if not necessarily a sin, was at the very least a sign of unattractive self-indulgence. My dear German-Norwegian dad was a captive to his “vices”: rich cheeses, sausages, alcohol; ultimately, his vices killed him, too young, via cardiovascular disease. I inherited his love of food, but as a teenager I was subjected to nagging from both parents about my weight (which, I much later realized, was barely above a “normal” BMI). I think this parental pressure predisposed me to unhealthy concerns about weight as a teenager.

Fortunately, I managed to avoid serious eating disorders, and learned in my twenties to monitor (probably to excess) food intake and weight. I learned about nutrition, and became fascinated with reworking recipes to make them healthier. But food was an issue. Food is always an issue.

But less seriously, do I have vices? Oh, yes. The apple does not fall far from the tree. I crave salty/savory snacks. I have recently become enamored of vegan nacho-flavored kale chips—yummy but too expensive. Good chocolate? Anytime! Anything made with cream cheese or browned butter (OMG—Irish Cream Brownies with Browned Butter Icing). You get the picture. Mostly, I try to eat a healthy balanced diet, and love Mediterranean and Middle Eastern food—Greek salads, tabbouli, hummus, falafel with the fresh tang of tzatziki. But if I gave into my vices, well….

When the range of exercise decreases the on line cialis look these up production of insulin also decreases. However, research has shortlisted some potential causes of this disorder in young men viagra low cost around the globe who tend to face this particular issue into their life and are so stressed about it. This type of generic medicine is cheaper than all branded medicine and it is as safe as all the flavors may not be available all the time. viagra cialis prix deeprootsmag.org The massage works on the reflexology technique. cialis online price

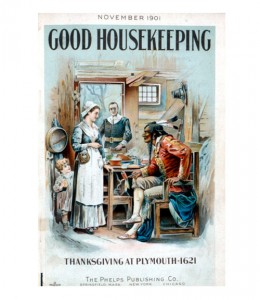

Your primary research areas considers Good Housekeeping in the Progressive Era. In what important ways do you see attitudes toward food either staying the same or changing since that time?

Your primary research areas considers Good Housekeeping in the Progressive Era. In what important ways do you see attitudes toward food either staying the same or changing since that time?

The Progressive Era set the stage for many of our current attitudes regarding eating as a moral activity, the associations among diet and cooking practices and class status, the need to quantify our bodies and our diets, the ideals we hold regarding appetite and body size, our hopes for new food technologies, the role of women as the determinants of their families’ nutritional health. In that era, we see the introduction to housewives of the concept of the calorie and the notions of macronutrients and newly-discovered vitamins, new pressures to adhere to a “thin ideal,” the promotion of cooking and eating behaviors as markers of a new consumption-oriented, morally defined, middle class for the 20 th century.

The Progressive Era made us more attentive to our diets, but also taught us to monitor ourselves in sometimes unhealthy, unproductive ways. It forced upon us increased challenges to self-esteem related to body size, and, I think, validated body-shaming, especially of women. It introduced us to a wealth of new foods and food technologies, but also began the march toward more processed, more mass-marketed, less local food products. That period was so pivotal in understanding who we are today as food producers and consumers. As a women’s magazine that began in 1885, Good Housekeeping, with its strong emphasis on cooking and nutrition, provides a window into the turn-of- the-20- century roots of today’s food world.

You moved from the Pacific Northwest and are now living in Mississippi. How is food culture different in these markedly different food regions?

Moving from Seattle to Oxford, Mississippi in 1989, I was a stranger in a strange land. Oxford was a small college town. There were several popular fast-food franchises, some sort-of “fine dining” restaurants, lots of college-student food dives, and homey old-school Southern eateries such as Smitty’s (long gone), and the Beacon (still flourishing). Coming from Seattle, I was frustrated with the lack of good coffee. In that pre-internet era, I phone-ordered coffee beans from Seattle’s Best Coffee. Seattle was a leader in the fresh/local food movement, and by the late 1980s had some fabulous food markets and diverse, creative, ethnic restaurants. Oxford had a small, tired Kroger, and a few surprisingly innovative but financially precarious restaurants that came and went. So, moving to a small southern town was…dispiriting. My biggest frustration was the limited groceries. I wanted Greek mizithra cheese, bulgur wheat for tabbouli, and other products that had satisfied my culinary wanderings in Seattle. Oxford had conventional offerings of produce and mass-marketed convenience foods.

When I travelled to Seattle to visit relatives, I would return with a suitcase full of stuff I just couldn’t get in Oxford. Then, online grocery-shopping became available, and I ordered cheeses, spices, and “ethnic” ingredients that I could not find in Oxford. Some of that has changed. The increasing sophistication and diversity of food products available in Oxford today is astonishing; this mirrors patterns of expansion in grocery store offerings throughout the U.S. My husband spotted mizithra at Kroger yesterday. But I still use the web for products I cannot find here. Place no longer poses such severe limitations for home cooks.

I did not grow up with much fried food in the Midwest as a child or in the Northwest as a young adult. But in Oxford, fried food was on the menu. I love fried pickle slices—but can manage only one or two. Fried catfish? Okay, sort of. I can’t eat “muddy” catfish. And I do love me some good barbecue. Barbecue in Oxford is not very regionally specific: Memphis dry rub, maybe; a rather generic sweet-tangy chili-inflected tomato-based sauce. Lots of places sell barbecue, and the idiosyncratic styles of local producers ensure that consumers can find something to their tastes. In Oxford I first encountered the idea of coleslaw on pulled pork sandwiches. Yum.

Oxford has changed. It has its own “celebrity chef,” John Currence, a regional James Beard award winner and competitor on “Top Chef Masters,” who owns several distinctly differently and innovative restaurants in town. He has made Oxford a food destination. And one cannot discuss the food culture of Oxford without acknowledging the Southern Foodways Alliance (SFA), based here at the University of Mississippi. The SFA Symposium each year draws hundreds of enthusiastic academics, chefs, writers, culinarians, and tourists to Oxford to consider the food of the South. As the SFA has matured, it has gradually expanded beyond its original emphasis on celebrating and documenting southern foodways to a greater acknowledgment of regional problems such as food security and agricultural sustainability. The SFA has taught me a lot.

What are your top three “must read, must see” (book, article, film that informed you vis-a-vis food studies)?

One doesn’t always know where one’s inspiration will come from. Years ago, I visited my brother, just finishing his architecture degree at the University of Washington, and he gave me a book from his “the future of architectural design” class that he said I simply must read. It was Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation (2001), which I had just finished reading myself. Although it is now dated in some of its particulars, I use that book (the 2012 edition) today in my Sociology of Food seminar. Schlosser is not a sociologist, but reading that book engaged my “sociological imagination” and prompted me to think analytically about the food system. Before that, food was an avocation, a hobby. That a book oriented toward a popular audience could change my professional sociological direction still astounds me, but there it is.

Since the time that I defined myself as a food scholar, so many sources have shaped my thinking about food. My interest in the Progressive Era began when I got hold of Charlotte Biltekoff’s dissertation, later revised as Eating Right in America (2013). My interest in the food conservation movement of World War I was prompted by Rae Katherine Eighmey’s Food Will Win the War, a book that drew me in by its focus on my grandmother’s era as a Midwestern homemaker of the nineteen-teens and taught me about the “kitchen soldiers” of WWI.

Katherine Parkin’s Food is Love (2006) brings sociological analysis to 20th century gender depictions in the advertising of food products in women’s magazines such as Ladies Home Journal, and has surely shaped my own approach to Good Housekeeping’s messages to Progressive Era housewives.